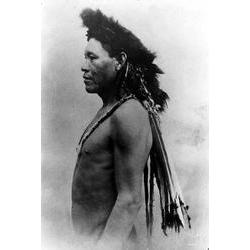

MAKUXI

HISTÓRICO DO CONTATO

Aldeamentos

A ocupação colonial portuguesa do vale do rio Branco data de meados do século XVIII. Foi uma ocupação marcadamente estratégico-militar. Nessa região, limítrofe às possessões espanhola e holandesa nas Guianas, os portugueses procuraram impedir possíveis tentativas de invasão a seus domínios no vale amazônico, construindo, em 1775, o forte São Joaquim, na confluência dos rios Uraricoera e Tacutu, formadores do Branco, via de acesso às bacias dos rios Orinoco e Essequibo.

A estratégia utilizada pelos portugueses para assegurar a posse do vale baseou-se no aldeamento dos índios efetuado pelo destacamento do forte. Para tanto, os militares portugueses distinguiam dentre a população indígena os Principaes e suasNações, buscando convencê-los, por meio de armas e presentes, das vantagens e desvantagens de trazerem as gentes de suas respectivas Nações para formar os aldeamentos.

As informações disponíveis sobre o contato com os Macuxi nesse período são raras e fragmentárias. Surpreendentemente, das diversas etnias então aldeadas, os Macuxi comparecem em pequeno número: temos notícia de apenas dois Principaes Macuxi: Ananahy em 1784 e Paraujamari em 1788, que chegaram a aldear-se, trazendo pequenos grupos consigo. No entanto, não permaneceriam por muito tempo nos aldeamentos. Logo após estas notícias, em 1790, Parauijamari seria acusado de liderar uma grande rebelião, quando a maior parte dos índios aldeados fugiu e os remanescentes foram espalhados por outros aldeamentos portugueses no rio Negro.

Tal revolta poria fim à política oficial de aldeamento e não seriam empreendidas novas tentativas de colonização naquela área ainda no século XVIII. Porém, são muitas as evidências de que as expedições de recrutamento forçado da população indígena permaneceram atuantes, motivadas por outros interesses que se estabeleceriam na região, causando grande impacto sobre a demografia e a territorialidade dos Macuxi.

Extrativismo

Uma nova fase do contato, que viria afetar mais drasticamente o conjunto da população Macuxi, teria início no século XIX, com a expansão da exploração da borracha na Amazônia e, em especial, com a extração do caucho e da balata na matas do baixo rio Branco. A arregimentação dos índios destinava-se, principalmente, à área do rio Negro, mas também houve “descimentos” para o próprio vale do rio Branco, onde eram engajados como força de trabalho no extrativismo.

Tais empreendimentos de caráter privado imprimiram a tônica das relações interétnicas no período. Embora o governo imperial demonstrasse uma constante preocupação quanto à implementação de uma política indigenista oficial nessa zona de fronteira, os registros administrativos disponíveis revelam a sua grande debilidade nesse campo. Já nas últimas décadas do século XIX, em particular após a República, que veio a conferir maior autonomia à administração local, ao aproximar-se o auge do ciclo da borracha os regionais passavam a ser considerados colaboradores necessários para a colonização regional: detentores do comércio e dos meios de comunicação com o interior, os regatões [aqueles que trocavam produtos manufaturados pelos de extração diretamente junto à população indígena e regional] ali reinavam.

Pecuária

Parece haver uma estreita conexão entre o extrativismo no baixo rio Branco e a pecuária que viria a se consolidar no curso alto desse rio: o capital extrativista viria a financiar a pecuária. Em contrapartida, a pecuária incipiente estabelecida nos campos do alto rio Branco favorecia o recrutamento da força de trabalho dos índios na região, a qual não se limitava à extração, mas compreendia todas as atividades correlatas, em particular a navegação do rio. Havia ampla margem de liberdade para os regatões e quaisquer outros empresários atuantes na área para penalizar os índios e forçá-los ao trabalho. Não havia instância que os penalizasse pela escravidão a que, na prática, submetiam os índios.

Correlata ao trabalho forçado, a migração igualmente forçada singulariza esse momento histórico, uma vez que as migrações entre a população indígena no alto rio Branco decorriam muito mais da expulsão da terra pelo avanço da pecuária do que pelo deslocamento compulsório da mão-de-obra.

Na virada para o século XX, a engrenagem de recrutamento de mão-de-obra indígena montada nas décadas anteriores persistia, apesar de decadente. Aldeias abandonadas e movimentos de fuga provocados pela chegada dos brancos não foram somente registrados pelos cronistas do rio Branco, mas foram igualmente objeto de registro por parte dos Macuxi e permanecem ainda hoje em sua memória, marcados por um momento dramático nas diversas narrativas que versam sobre sua história política.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου